CALL NAME Profession

W0ORE Tony England Astronaut

K1JT Joe Taylor Scientist

K1OKI Mickey Schulhof Heads SONY US

KB2GSD Walter Cronkite TV Journalist

K2HEP John Sculley former CEO of Apple Computer

KB2LHI Joe Walsh sk “World’s Fastest Shooter”

WA2MKI Larry Ferrari sk Musician/TV personality

K2ORS Jean Shepard sk TV personality

W2TQ Joel Miller Attorney

K2ZCZ George Pataki Governor of New York 1994

W4CGP Chet Atkins Singer/Songwriter

WB4KCG Ronnie Milsap Singer/Songwriter

N4KET David French TV Journalist

K4LIB Arthur Godfrey sk TV personality

KC4OCA Gordon Barnes Meteorologist

N4RH Ralph Haller Former FCC PRB chief

WA4SIR Ron Parise Astronaut

WD4LZC Larnelle Harris Country Music Singer

WD4SKT 14.230 MHz SSTV

KD4WUJ Patty Loveless Country Music Singer

W4ZG Worth Gruelle Author

K4ZVZ Paul W. Tibbets Dropped the First Atom Bomb on Hiroshima

W5LFL Owen Garriot Astronaut

N5QWL Jay Apt Astronaut

KC5ZTA Koichi Wakata Astronaut from Japan

WB6ACU Joe Walsh Singer/Songwriter – Eagles

K6DUE Roy Neal TV personality

K6DXK Ernest P. Lehman Writer, Producer, Actor, Director

W6EZV Gen. Curtis LeMay Military legend

N6FUP Stu Cooks Baseball player

N6GGM Laura Cooks XYL of N6FUP

N6KGB Stewart Granger Actor

KB6LQR Jeana Yeager Pilot/Adventurer

KB6LQS Dick Rutan Pilot/Adventurer

AI6M Barry Friedman 2-time World Champion Juggler

W6OBB Art Bell Radio personality

KB6OLJ Paul J. Cohen Mathematician

KD6OY Garry Shandling TV Personality

W6QUT Freeman Gosden sk Actor

W6QYI Cardinal Roger Mahony Cleric

WB6RER Andy Devine Actor

W6ZH Herbert Hoover, Jr. sk Son of U.S. President

W7DUK Nolan Bushnell Computer Pioneer, Founded Atari

KG7JF Jeff Duntemann Author

K7TA Clifford Stoll Scientist/Author/Actor

NK7U Joe Rudi Baseball player

K7UGA Barry Goldwater sk US Senator

W8JK John Kraus Astronomer

W8PAL Al Gross sk Communications Pioneer/Inventor

9K2CS Prince Yousuf Al-Sabah Royalty

9N1MM Fr. Marshall Moran Renowned Missionary

CN8MH King Hassan II sk King of Morocco

EA0JC Juan Carlos King of Spain

FO5GJ Marlon Brando SK Actor

GB1MIR Helen Sharman Astronaut

G2DQU Sir Brian Rix Actor/Philanthropist

G3YLA Jim Bacon TV Meteorologist

HS1A Bhumiphol Adulayadej King of Thailand

I0FCG Francesco Cossiga former President of Italy

JI1KIT Keizo Obuchi Former Prime Minister of Japan

JY1 King Hussein King of Jordan

JY1NH Queen Noor Queen of Jordan

JY2HT King Hussein’s brother Former Crown Prince Hassan

JY2RZ Prince Raad Royal Jordan Radio Amateur Society

LU1SM Carlos Saul Menem President of Argentina

OD5LE Emil Lahoud President of Lebanon

SU1VN Prince Talal Saudi Arabian royalty

UA1LO Yuri Gagarin First Cosmonaut

U2MIR/UV3AM Musa Manarov Cosmonaut

VK2KB Sir Allan Fairhall Statesman

VK4HA Harry Angel sk at 106 Was Australia’s oldest radio amateur

VU2RG Rajiv Ghandi sk late Prime Minister of India

VU2SON Sonia Ghandi XYL of VU2RG

XE1GC Guillermo González Camarena Invented color television picture tube

XE1GGO Enrique Guzman Singer

XE1K Walter Cross Buchanan ex-Minister of Communications

XE1MMM Jorge Vargas Singer

XE1N Manuel Medina Built first spark transmitter in Mexico

YU1RL Radivoje “Rasa” Lazarevic Yugoslav ambassador to Brazil

Category Archives: Amateur Radio General

DX Net Rant by ZL3JT

In the beginning, when God created radio, some people, including me, found that I could “work DX” on a “DX net”. In fact I went on every net I could find to satisfy my thirst for new countries and Islands in the IOTA program.

I looked up to people like Jim Smith VK9NS, Roy Jackson ZL4BO, N6FF Dick Wolf, Dr Saleem OE6EGG, Zedan Hussein JY4ZH, Percy Anderson VK4CPA… who ran these splendid sessions for those who thought it was a hellava good idea to be involved.

Little pistols with bits of wire got a chance at some “real” DX, if and when they also joined in these nets on 20m and 15m or 40m The oldest and “best” was the ANZA net on 21.205 When I had my “novice Morse” I used to listen with anxiety to the activity generated each day on the 15M ANZA Net knowing that I couldn’t participate because it was out my of my allocated frequencies… It sure was incentive to pass the Morse test and upgrade to a full call……

But over time, a couple of years or so, I realized that there was no challenge working DX with someone supervising the QSO…Saying “Over rover” at the appropriate time. …Repeat his report…You’ve got the number wrong!. But if that’s the way you want to do it, who am I to criticize? I did it…then I got into using Morse code for DXing…..

Things changed dramatically in my mind…I could do it myself…All by myself…. It’s much more satisfying…and it’s bloody difficult to run a net on CW… So I got my DXCC Honour Roll all by myself, mostly with CW… I didn’t have to count any of the QSOs I had done on DX nets which was even more satisfying…But that’s just my way.

For something to do, I went on SSB nets as a DX station…It was good to do that for those who only work DX nets. But DX is where you find it …every time…. If it’s on a net, then join the net, work the DX station if you want…. What the hell does anyone else care? It’s nobody else’s business how you work DX. But I bet you won’t find nets on all bands, you will seldom find a DXpedition on a net….. So you have to forget nets, and join the pile up…

Pile ups are inversely proportional to the rarity of the DX station…remember that because you have to get craftier….. You have to make your own luck in a pile up!

73 and GD DX

Duncan, ZL3JT

My Favourite DX Stories by W4KVS

My Favourite DX Stories: Notes From a Beginning DXer

By Kim Stenson, W4KVS

[email protected]

You don’t have to spend a lot of money on a plane ticket to travel the world. From the comfort of your own shack, you too can be a globe-trotter. All you need is a radio, an antenna and the desire to make that QSO. By seeing the world through your radio, you get the QSL card without the jet lag!

Like most DXers, I enjoy reading about (and working) DXpeditions to exotic parts of the world. I have also found that there is a great deal of adventure on my end of the microphone. One of the great attractions of Amateur Radio is the ability to contact fellow operators in distant lands. Accordingly, I find a great deal of pleasure in reading about the DX adventures of hams, especially those with modest equipment. With 100 W and a modest antenna system (wires for HF and a small 3 element beam for 6 meters), I have had my share of exciting DX stories. Here are some of my favourites.

Listen to the Whole Call

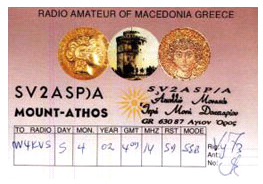

One evening I was tuning around 20 meters when I came across a station calling CQ. As the operator announced his call sign I immediately recognized the SV prefix as Greece; my first impulse was to keep tuning as I already had worked several SV stations. For whatever reason, I decided to remain on the frequency and to listen carefully to the call — I soon realized there was something different. The operator was adding “stroke alpha” after his call. I recognized that it was Mount Athos, one of the rarest DXCC entities. I had recently read that Monk Apollo, SV2ASP/A, the only licensed HF operator at the religious enclave on the Aegean coast. To my knowledge, he had been off the air for at least a couple of years, and I thought my chances of ever getting Mount Athos were next to impossible.

One evening I was tuning around 20 meters when I came across a station calling CQ. As the operator announced his call sign I immediately recognized the SV prefix as Greece; my first impulse was to keep tuning as I already had worked several SV stations. For whatever reason, I decided to remain on the frequency and to listen carefully to the call — I soon realized there was something different. The operator was adding “stroke alpha” after his call. I recognized that it was Mount Athos, one of the rarest DXCC entities. I had recently read that Monk Apollo, SV2ASP/A, the only licensed HF operator at the religious enclave on the Aegean coast. To my knowledge, he had been off the air for at least a couple of years, and I thought my chances of ever getting Mount Athos were next to impossible.

Knowing that the airwaves would soon erupt into a frenzy, I frantically threw my call in, “W4KVS.” The operator only copied part of the call and came back with, “W4, W4?” Not knowing whether he had heard me or another W4 station, I again threw out my call, “W4KVS, W4KVS.” To my great surprise, he came back to my call and we had a short exchange. I asked him if I was speaking to Monk Apollo and he confirmed that it was indeed him on the other end. As soon as I signed off, a huge pileup ensued, one that I had no chance of breaking if I had not been the first to call. This contact is a good example of listening to the whole call. If I had not listened carefully, I might have dismissed the call as a routine SV station and missed an extraordinary DX opportunity.

Out of Africa

A similar situation took place on 10 meters one Saturday morning in winter when I came across a 3DA (Swaziland) working a huge pileup; 3DA0WPX was working simplex, and after the operator announced, “QRZ?” all I could hear was a giant whine. Any attempt to make a contact would be futile, as there was absolutely no way I could get through the pileup. I had never heard 3DA before and there was no telling when I would have another chance. Disappointed and somewhat frustrated, I moved on. Later that afternoon I was tuning 10 meters again, and suddenly I heard 3DA0WPX calling CQ again. Frantically, I answered his CQ and Andre came back to me with “You are 59, nice signal.” I also gave him a 59 report, but resisted the urge to tell him I was using an attic antenna. Within seconds, the frequency erupted into what seemed like hundreds of signals, most of which, I am quite sure, were stronger than mine.

A similar situation took place on 10 meters one Saturday morning in winter when I came across a 3DA (Swaziland) working a huge pileup; 3DA0WPX was working simplex, and after the operator announced, “QRZ?” all I could hear was a giant whine. Any attempt to make a contact would be futile, as there was absolutely no way I could get through the pileup. I had never heard 3DA before and there was no telling when I would have another chance. Disappointed and somewhat frustrated, I moved on. Later that afternoon I was tuning 10 meters again, and suddenly I heard 3DA0WPX calling CQ again. Frantically, I answered his CQ and Andre came back to me with “You are 59, nice signal.” I also gave him a 59 report, but resisted the urge to tell him I was using an attic antenna. Within seconds, the frequency erupted into what seemed like hundreds of signals, most of which, I am quite sure, were stronger than mine.

It’s not Easy being Greenland

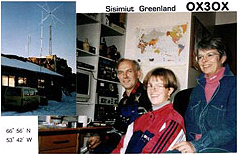

Pileups sometimes appear insurmountable but they often have ebbs and flows. A huge pileup can be in progress and then drop to a manageable level, only to be soon followed by another huge pileup. One morning I heard OX3OX in Greenland on 6 meters SSB working a fairly large pileup. The prefix OX is not that common on HF, and on 6 meters it is a real catch. I started throwing my call in; at the time, I was only using an omnidirectional loop antenna. After calling for a while, the pileup seemed to be getting smaller, and instead of handing out 59 reports, Ole, OX3OX, started giving out 55 reports, and finally 51 reports. The weaker stations were getting through, but could he even hear me? Finally, he did hear part of my call. After several repeats, Ole was finally able to copy my call and I exchanged reports with him. My report was 33 — not great by any definition, but I was able to get OX on 6 meters. As I often do, I listened for a while after the contact. He continued to call CQ, but did not raise anyone. I had been on the bottom of the pileup.

Pileups sometimes appear insurmountable but they often have ebbs and flows. A huge pileup can be in progress and then drop to a manageable level, only to be soon followed by another huge pileup. One morning I heard OX3OX in Greenland on 6 meters SSB working a fairly large pileup. The prefix OX is not that common on HF, and on 6 meters it is a real catch. I started throwing my call in; at the time, I was only using an omnidirectional loop antenna. After calling for a while, the pileup seemed to be getting smaller, and instead of handing out 59 reports, Ole, OX3OX, started giving out 55 reports, and finally 51 reports. The weaker stations were getting through, but could he even hear me? Finally, he did hear part of my call. After several repeats, Ole was finally able to copy my call and I exchanged reports with him. My report was 33 — not great by any definition, but I was able to get OX on 6 meters. As I often do, I listened for a while after the contact. He continued to call CQ, but did not raise anyone. I had been on the bottom of the pileup.

Persistence Pays Off

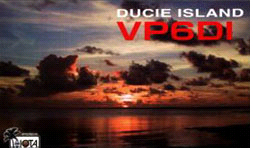

Just like everyone else, I was excited about the first DXpedition to Ducie Island, VP6, hitting the airwaves — it would be the first station to operate in a new DXCC entity. I, however, had my doubts about working it. Everyone needed Ducie Island, and I expected the pileups to be far worse than any I had yet encountered. After all, everyone needed this one. I believed my best chance of making a contact would be toward the end of the DXpedition.

Just like everyone else, I was excited about the first DXpedition to Ducie Island, VP6, hitting the airwaves — it would be the first station to operate in a new DXCC entity. I, however, had my doubts about working it. Everyone needed Ducie Island, and I expected the pileups to be far worse than any I had yet encountered. After all, everyone needed this one. I believed my best chance of making a contact would be toward the end of the DXpedition.

One weekend afternoon, I heard VP6DI on 15 meters SSB. The operator was working a fairly wide split above his calling frequency, and I tried to determine his pattern by switching VFOs; however, I could hear very few stations calling because both the calling stations, and Ducie were located west of my location. If you cannot hear the calling stations, it then becomes difficult, if not impossible, to determine the DX station’s operating pattern.

I took the best action I could — I planted myself on what I thought to be a clear frequency and started calling. I tried for an hour or so, but I was not successful and so I gave up, believing it futile to keep calling. I turned the dial and began looking for other DX. I searched the band for a while and did not find anything interesting, so I decided to go back to chasing Ducie. I again found what I thought was a clear frequency and made a call. VP6DI came back to another call and then I heard “QRZ?” I made another call, and suddenly VP6DI came back with, “W4KVS, 59.” I shot back with a report and then revelled in my success. I still have trouble believing I actually worked VP6DI under those conditions.

Getting Guam

Asia and the Pacific area are very difficult from my location in South Carolina, and any contacts in those areas are hard to come by. Guam was one country I almost never heard, and I was very excited to hear AH2R on 15 meters during a contest.

Asia and the Pacific area are very difficult from my location in South Carolina, and any contacts in those areas are hard to come by. Guam was one country I almost never heard, and I was very excited to hear AH2R on 15 meters during a contest.

It was the second day of the contest with only an hour to go, and AH2R was not getting many calls. It looked like I was going to be able to bag a new one fairly easily. I threw in my call literally dozens of times, but AH2R was not hearing me. Occasionally, the operator would catch part of my call and ask for “W4” or “VS.” Frustrated that he was not able to get the entire call, I decided to throw in the towel. I looked at my watch and there was only about 10 minutes left in the contest. Then I thought to myself, “Why not continue for the next 10 minutes — what do I have to lose?”

I continued calling with the same results: the operator would hear “W4” or “VS,” but not my entire call. The clock continued to tick and finally there were only a few seconds left before the contest ended. I had time for one last, most likely, futile attempt and made the call, “W4KVS.” Incredibly, AH2R came back with, “W4KVS, 59.” With that, the contest ended, but I had a new country.

Stuck in the Middle

One of the most exciting aspects of DXing is finding the unexpected. One Saturday morning, I heard a fairly weak station calling CQ on 20 meters. The station had strong audio, but it was sandwiched between two very loud stations. No one was answering the CQ and the interference was troublesome, but I had a feeling that this might be something out of the ordinary. From within the interference, I finally managed to copy the station, 4W6MM. East Timor was, and remains, one of the rarest DXCC entities, and I never thought I had a chance of working the one active station located in that country.

One of the most exciting aspects of DXing is finding the unexpected. One Saturday morning, I heard a fairly weak station calling CQ on 20 meters. The station had strong audio, but it was sandwiched between two very loud stations. No one was answering the CQ and the interference was troublesome, but I had a feeling that this might be something out of the ordinary. From within the interference, I finally managed to copy the station, 4W6MM. East Timor was, and remains, one of the rarest DXCC entities, and I never thought I had a chance of working the one active station located in that country.

Two thoughts immediately raced through my mind. First, 4W6MM was not very strong. In the clear, I could hear him, but it was quite likely that he would not be able to copy my signal at all. It would be very frustrating to hear a rare DX station calling CQ with no one answering and him not being able to hear me. I could have a another possible AH2R situation on my hands. Second, I would have to time my call just right. I might be able to hear him with one of the strong adjacent stations transmitting, but not with both at the same time.

I listened for a few seconds and suddenly there was a lull in the noise. I quickly threw in my call, and to my great surprise, 4W6MM came back with “W4KVS, 59” just as one of the adjacent stations started transmitting again. Nevertheless, I shot back his report, which he acknowledged. Incredibly, I heard 4W6MM the following Saturday in a contest and was able to work him again. Both contacts lasted only a few seconds, but they were definitely among my most memorable.

Sometimes You Feel Like a Nut…

St Peter and Paul Rocks is also one of the most sought-after DXCC entities. It is a place that is seldom activated; I had never even heard a station from this Brazilian island. Joca, PS7JN, periodically operated from this remote island, but he worked primarily RTTY. I was set up to work RTTY with my computer sound card and interface, but I had never been able to have a successful RTTY contact. The few times I had tried, I was not able to make a contact.

St Peter and Paul Rocks is also one of the most sought-after DXCC entities. It is a place that is seldom activated; I had never even heard a station from this Brazilian island. Joca, PS7JN, periodically operated from this remote island, but he worked primarily RTTY. I was set up to work RTTY with my computer sound card and interface, but I had never been able to have a successful RTTY contact. The few times I had tried, I was not able to make a contact.

Toward the end of one of his mini-DXpeditions, I noticed that that ZW0S, a Brazilian special event call sign, was frequently spotted, but with relatively few callers. Now was the time to see if I could work St Peter and Paul. I turned on my computer and brought up the RTTY software. I tuned for ZW0S, and suddenly he appeared on my screen. I hit the macro and transmitted, “DE W4KVS W4KVS W4KVS.” Immediately, ZW0S came back with “W4KVS 599 599.” I happily gave Joca his report and completed my first RTTY contact, which just happened to be a rare DXCC entity.

“Snappy Operators on a Completely Quiet Band”

Cameroon, TJ, is another country high on the DXCC most wanted list and I was glad to find out that Roger Western, G3SXW, and Nigel Cawthorne, G3TXF, planned a DXpedition there in the spring of 2004. One evening, I was able to copy Roger, TJ3G, on 20 meters CW working split. There was a pretty good pileup, but I kept throwing my call in. After some time, Roger indicated he would be taking a short break. I stayed on the frequency, hoping some of the others would not come back. It worked. In a few minutes, Roger came back and I got him on the second call. I was also able to work Nigel on 17 meters near the end of the DXpedition. Two great contacts!

Cameroon, TJ, is another country high on the DXCC most wanted list and I was glad to find out that Roger Western, G3SXW, and Nigel Cawthorne, G3TXF, planned a DXpedition there in the spring of 2004. One evening, I was able to copy Roger, TJ3G, on 20 meters CW working split. There was a pretty good pileup, but I kept throwing my call in. After some time, Roger indicated he would be taking a short break. I stayed on the frequency, hoping some of the others would not come back. It worked. In a few minutes, Roger came back and I got him on the second call. I was also able to work Nigel on 17 meters near the end of the DXpedition. Two great contacts!

Later, both Roger and Nigel said they thought 20 meters would be their best chance to find suitable propagation, providing long openings to all areas, and they enjoyed the “snappy operators on a completely quiet band.”

Even with a modest setup, you can have a lot of fun DXing. SSB, CW and RTTY on both HF and VHF have allowed me to participate in some great DX encounters. DXing is an adventure, and I can’t wait for my next DX experience. I know it is out there.

Kim Stenson, W4KVS, is an Amateur Extra, first licensed in 2000. Retired from the US Army, Kim is a former infantry officer who saw combat in the Persian Gulf; he counts the Bronze Star and Combat Infantry Badge among his military honors. Kim received his BA from Washington and Lee College in Virginia, and his MA from Norwich University. He is presently chief of the Preparedness and Recovery Branch of the South Carolina Emergency Management Division.

Audio Dynamic Range

Audio Dynamic Range

What is you audio dynamic range? This mostly applies to SSB transmissions but could also apply to FM and AM as well. Simply put it is the difference between no modulation during key down and your modulation peak in dB.

Your dynamic range listed below will give you an idea on how your audio is perceived by the other contact.

- 10 dB, which is very harsh and tiring to listen too. Much background noise including fans, road noise, air-conditioning, dogs barking and in general background clutter noise. Your contact will ask for repeats a lot and in general your QSOs will be short.

- 20 dB, decent audio range with a little audio background noise. QSO’s will last longer. Very little repeats. Most stations fall into this category.

- 30 dB, your contacts will complement you on you audio, tonal quality aside; you will find folks will like to listen to your transmissions. Communications in weak conditions will be generally more successful.

- 40 dB, you are now into broadcast quality transmissions. This is not easy to obtain but with proper microphone techniques and mic gain settings most any transceiver can obtain this level.

- 50 dB, this is where you need to be if you plan on running a Linear Amplifier. With a +30 dB over S9 signal to your contact, your un-modulated signal will still be an S6 on their receiver. Poor dynamic range is the reason people ask if you are running a linear amplifier.

For FM you will need a deviation meter but with a good oscilloscope you could use the same method as you would use for AM. For AM you will need an oscilloscope to look at voltage level from no modulation and modulation peaks. For both FM and AM, this can be derived from a monitor receiver speaker output. SSB is much easier. Look at the peak signal as monitored from a nearby station. The difference in the peak reading to your modulating signal to the level received while not modulating is the dynamic range. If you have a lab grade watt meter you can look at the power output from the radio or amplifier. The formula is:

Log (power max/power min) x10 =DynamicRangein dB.

An example of a 1500 watt signal with a non modulation level of 100 mW is shown below:

Log (1500/.100) x10 = 31.76 dB

As you can see, 100 millawatts can transmit quite a lot of signal or noise. Some of this noise could be generated in the transmitter but generally it is from the microphone environment. To check you audio level, transmit into a dummy load and watch the output with no modulation. If you see a level indicated, turn you microphone gain down to zero. If the level drops to zero your microphone level is the problem with your low dynamic range and your audio environment.

Several things can be done to improve you dynamic range.

- Try to pick a quiet place for your station.

- Close the door to your shack.

- Use the microphone between 3 and 6 inches from your lips.

- Your ALC should read 10 dB or less.

- Avoid excessive compression. It is mostly microphone gain with a little filtering.

- Speak directly into the microphone, not on the side.

- Use a wind-screen (foam rubber) over the microphone.

- Be aware of cooling fan noise. Placement of fan related gear (amplifiers) is important.

- Use a suspended microphone. They pick up less desk noise and vibration.

- Avoid a room that has no rugs or drapes. Echoes don’t help and can make communication quality very poor.

- Make sure the TV and stereo cannot be heard.

These are the most prevalent items I hear being done in QSOs. If you’re mobile, roll up your window. Some FM mobiles have so much vehicle and wind noise their transmissions are unintelligible.

These are just a few suggestions on making your home station and mobile environment much more pleasant to listen to. Work with other hams for a critical ear. Now have fun.

Mike Higgins – K6AER

The Phonetic Alphabet

The Phonetic Alphabet

A: Alfa N: November

B: Bravo O: Oscar

C: Charlie P: Papa

D: Delta Q:Quebec

E: Echo R: Romeo

F: Foxtrot S: Sierra

G: Golf T: Tango

H: Hotel U: Uniform

I: India V: Victor

J: Juliet W: Whiskey

K: Kilo X: X-ray

L:Lima Y: Yankee

M: Mike Z: Zulu

Do All the Digital Modes, Cheap!

Do All the Digital Modes, Cheap!

By Scott N4ZOU

The solar cycle is winding down and the higher HF bands get poorer by the week. Even the 20-meter band closes down pretty early in the evening, sometimes even the afternoon! You go to the digital modes area where you might find a few PSK-31 stations but copy is really poor with the band in and out. You drop to 40 meters and try that band but between the high noise level and the SSB DX even if you managed to find another operator there you had a very hard time understanding what the other station was sending due to the lost words.

If you have been around a few years you remember using Pactor in ARQ to get your message across even while the band is in and out for short periods or the noise is bad. If you have been a digital operator for 10 or more years you remember how great Amtor in ARQ was for getting that text across what some would assume was a dead band, you could not even hear the other stations Amtor noise in your speaker if you had it turned up but still the text was flowing, a little slow with lots of errors and re-sends but it was still working.

When PSK-31 and the other digital modes used with a computer sound card started the 20-meter and higher bands was just beginning to come alive with the solar cycle starting to rise. A lot of operators that had never used digital modes tried out the new sound card modes and even some of the old modes that the sound card could handle like RTTY and found them to be fun. Most of us already doing digital modes also enjoyed them and so a lot of the terminal controllers like the PK-232, KAM, and MFJ-1278 got taken out of line and an interface for a computer sound card that you already had got put in line. Some of us sold their terminal controller’s thinking that it was now outdated or put it in the closet to collect dust with some other out dated or boat anchor gear. I was guilty of that!

A few months ago when I figured out that the only modes that were going to allow me to operate and still have fun at it on 40 and 80 meters was Amtor and Pactor in ARQ error correcting mode. I dug out my old PK-232MBX and hooked it up and tried it out on RTTY mode on 20 meters and it still worked! I started looking around the band and found John W2LWB calling CQ in FEC Pactor. I entered the command to link to him and got it going and had a great time with a long chat that was error free. Then I remembered how fun old Amtor was and switched to FEC Amtor mode and called CQ with no luck at all for several hours. Then it hit me! Amtor was considered so out dated no one would even remember what the 100-baud signal would sound like and would never call me in that mode much less start an ARQ link.

I went back to Pactor mode a few weeks and also did a lot of RTTY operating. I ran into John K3KXJ in RTTY mode and noticed that in his brag file that he was running an old PK-232. So when it was my turn to key down and type I asked if he would like to switch to ARQ Amtor mode as the band was starting to get poor. We did switch modes and got the link going right off and we both had a great time chirping away. That’s when I built a interface box that would allow me to switch between the PK-232MBX and the computer sound card with just one DPDT switch on the front of the box containing all the required circuits for matching the audio between the sound card and the transceiver. It worked out very well. Not only did I have the modes in the PK-232MBX not available for use with the sound card but also with the flip of one switch I have access to the sound card modes! You can download a PDF format file containing all the information on building the interface box at http://www.geocities.com/n4zou/files/tnc-psk.pdf.

Now When I call CQ in RTTY mode I include that I can take Amtor links as well and give my Selcal Amtor ID used in starting a link. This works and I do get many ARQ Amtor links. You can read all about it at http://www.geocities.com/n4zou/files/amtor.pdf.

The old band plan for Amtor was from 14.065 to 14.085. Today 14.065 to 14.080 is used with Pactor MBO stations and Keyboard QSO’s and also PSK-31 is used around 14.071. This leaves 14.080 to 14.085 for shared RTTY and Amtor operation. All the bands except 10 meters, 160 meters and the WARC bands follow the same general agreements as to where and what mode is used.

Now we get to the interesting part of this story. Just how do you get on ARQ Amtor and Pactor modes without an expensive TNC? With a simple and cheap Hamcomm style modem also known as a Volksrtty modem connected to a RS-232 comport on your computer and run a DOS based program called Hamcomm 3.1 or Terman 93. I ran into Bill K0CDJ that had purchased a kit called a Volksrtty modem and was trying to get it to work in ARQ Amtor and the Hamcomm 3.1 program. We could start the link but after a minute or so it would start producing errors and then do a re-link to start sending text across again. It turned out to be a timing problem, which was corrected by monitoring the ARRL digital bulletins sent in FEC Amtor mode and compensating for the clock in the computer. After Bill corrected the timing problem we linked in ARQ Amtor mode a few days later with no errors! Bill said that he also has made several Pactor 1 links using the same Volksrtty modem and the Terman 93 program that also does Amtor and RTTY. We tried it and we linked in Pactor 1 and it did work very well. The only downside to using these programs is that they must be run under DOS.

Due to the critical timing required in these modes no other programs can be running in the computer so you can’t even run them in a DOS window while still having Windows running. If any program grabs CPU time while your ARQ linked to another station the link will shut down. When the link is running it’s like a chain driving a camshaft in an engine. If another program grabs CPU time then the chain just jumped a few notches and the engine dies, as the ARQ link will. The good part of this problem is that an old 386 and higher computer will run these programs just fine.

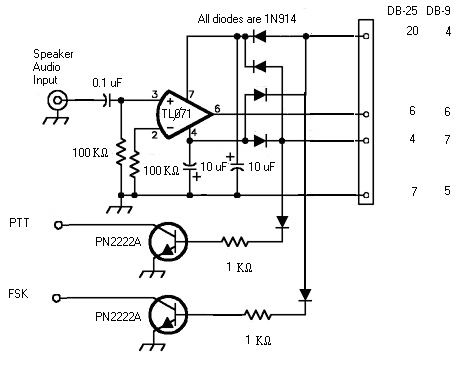

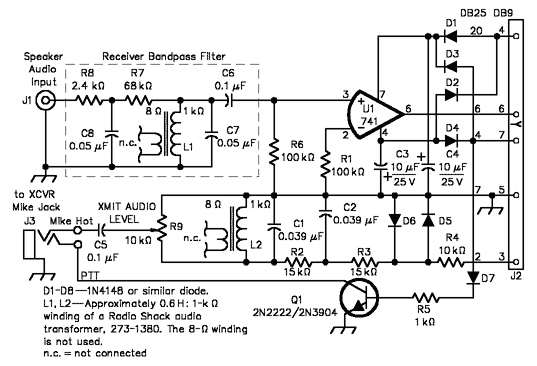

As no sound card is required you could find an old 386 Laptop computer for a few dollars and use it as a dedicated terminal for RTTY, Amtor, and Pactor. The Hamcomm or Volksrtty modem can be built for only a few dollars and will cost less than most sound card interface box’s using expensive isolation transformers. The interface consists of a 741 op-amp or for better performance uses a TL071 (T L ZERO seven one), PN2222A (2N2222) transistors, resistors, capacitors, and 1N914 diodes. The optional Band pass Filter is worth adding if you can’t use narrow filters suitable for FSK signals in SSB mode. I order all my parts from www.mouser.com. You can order by Internet, phone, or mail and use a credit card, check, or money order. The modem can be built several ways, FSK, AFSK, and optional audio filer included.

I just had to build one myself and try it out after talking to Bill. I built a really cheap one for use with my ICOM IC-756 PRO II. I already had everything required but even new parts from Mouser would only be $1.60! I did not use any audio filters in front of the TL071 as the DSP RTTY filter in the PRO II takes care of that. I also did not build the AFSK circuit, as you must use FSK in RTTY mode on the PRO II. The DTR pin on the RS-232 comport is for keying the FSK pin on the transceiver. RTS is used for the PTT circuit. This is very nice as it allows you to use the same comport for keying the transceiver if you also include circuits for use with a sound card.

If you can’t use FSK with your transceiver you will need to build a simple AFSK circuit that uses the same comport. You can leave off the FSK circuit if you like. This will connect to the microphone input pin or the audio in pin on the back of the transceiver.

Below is a schematic of a Basic + Hamcomm interface by K7SZL and is well worth the cost of the few extra parts required.

Using SSB mode on the transceiver will allow lots of noise along with the FSK signal to enter the OP-AMP so unless you can use a narrow filter in SSB mode the optional Receiver Band pass Filter should be built and placed between the transceiver audio output and the OP-AMP input to get the best performance from your modem. Here you could also use an external audio filter for the audio input to the OP-AMP such as an Autek Research QF-1A, Vectronics VEC-884, Timewave line of DSP Filters and even MFJ has Audio filters that can be adjusted to work just fine. If you already have something like one of the above products go ahead and use it, it can only help. Adjustment is easy, just bring up Hamcomm and the tuning display and find a station transmitting an FSK signal. Now adjust the filter so that only the Mark and Space tones show on the display.

All the circuits are non critical and can be built using dead bug style construction. I used a solder less breadboard mounted in a metal enclosure with different style connectors mounted on the back and a DPDT switch mounted on the front several years ago. This allows me to build different experimental circuits with little effort. I have been using this box for my TNC and sound card setup. For this project I un-plugged the sound card parts from the board and plugged in the Hamcomm parts. As I already have a TNC I don’t really need the Hamcomm modem so later I will be re-installing the sound card interface circuits. If you want you can order a circuit board from FAR Circuits that is designed for not only Hamcomm and Terman 93 but also other software programs.

The link to the ARRL article is http://www.kiva.net/~djones/n9art.pdf. This interface not only has the Hamcomm modem it also includes circuits for interfacing a sound card and the modes available for that type of modem such as PSK-31. If you do not already have a multi-mode TNC this is the way to get on all the modes. Mouser has prototype boards but there expensive. In this case a trip to Radio Shack might help out with the circuit board and enclosure. You could make it like I made mine and be able to experiment with different circuits and parts at a slightly higher cost or solder everything down and make it as small as you can for use with a Laptop and portable operation. You could even place it inside your computer! The back side of a comport connector could allow you to make your connections there and mount the entire project inside the computer and only have a transceiver connector mounted on the back.

For ICOM transceivers a DIN-5 plug and aMIDIcable would work great. Ten-Tec sometimes uses RCA jacks so if you have that setup RCA jacks mounted on the back of the computer case would allow standard cables for that. KAM TNC’s use a DB-9 connector on the back for connecting to a transceiver. You could remove the ribbon cable from the back of the comport connector and use it to connect to the modem and then go from the output of the modem back to the DB-9 connector and wire it up the same as the KAM. This would allow using KAM cables in your setup to the transceiver. Just figure out what would be the easy and cheap way to go with your setup.

Before you order the parts and build your interface you might want to use and older device that connected to computers in the past like the C-64. You might have one in the closet already! Included but not limited to this list is an AEA CP-1 or CP-100 computer patch. They are also cheap at anywhere from $10 for a CP-1 to about $20 for a CP-100. These are not real terminals but demodulators that do the same job as the simple Hamcomm modem but in a much better way. They have internal filters setup just for the mode your going to use and tuning displays.

They also use there own power supply and do not use power from the comport. Check and see if that old RTTY box in the closet works the same way. One thing to check is if the computer patch or RTTY box has an RS-232 port installed. Most of them only have TTL and so you must build a TTL to RS-232 converter to use them. Also the RS-232 connections are not standard, you cannot use a standard serial cable to connect them to your computer. The following link will take you to a good site where you can get the information you need to use the computer patches with Hamcomm or Terman93 http://www.klm-tech.com/technicothica/. From what I understand some Timewave DSP filters include FSK mode modulation and de- modulation circuits. You will need to check this and if true you might already have every thing you need. I don’t have a manual for them and they’re not available for download so I have no idea how they work.

Now you have no excuse not to get on all the available digital modes including the ARQ modes and not be limited to just the sound card modes or just a multi-mode TNC. Here are links to the software and some sites that also have lots of information on the Hamcomm and Volksrtty modems and software.

http://www.cqham.ru/volksrtty.htm

http://www.g7ltt.com/hamcom/hamcom.htm

http://www.g7ltt.com/hamcom/enhanced.htm

http://w1.859.telia.com/~u85920178/use/hc-00.htm

http://www.wd5gnr.com/hamcomm.htm

http://www.baycom.org/~tom/ham/terman93.zip This is the link to download Terman93.zip

http://www.pervisell.com/ham/hc1.htm Download the Hamcomm 3.1 software from this link.

Here is a Parts list from Mouser with Mouser part numbers. If you order all the parts including the optional audio filter and FSK circuit the total cost is only $8.40. I did not include a circuit board, cable, and enclosure as this depends on how you will want to use the modem and if you order the FAR circuit board and build the dual Hamcomm and sound card modem.

| Part | Description | Quantity | Mouser Part # | Price |

| U1 | TL071CN | 1 | 511-TL071CN | .40 |

| Receptacle | DB-9 pin | 1 | 156-1309 | .66 |

| Capacitor | .1uF | 2 | 140-PF2A104G | .63 |

| Electrolytic | 10uF | 2 | 140-L25V10 | .16 |

| Capacitor | .039uF | 2 | 140-PF2A393G | .56 |

| Capacitor | .05uF | 2 | 140-PF2A503G | .56 |

| Resistor | 100K | 2 | 30BJ250-100K | .22 |

| Trim pot | 10K | 1 | 323-409H-10K | .61 |

| Resistor | 15K | 2 | 30BJ250-15K | .22 |

| Resistor | 10K | 1 | 30BJ250-10K | .22 |

| Resistor | 1K | 1 (or 2*) | 30BJ250-1K | .22 |

| Resistor | 68K | 1 | 30BJ250-68K | .22 |

| Resistor | 2.4K | 1 | 30BJ250-2.4K | .22 |

| Diode | 1N914 | 7 | 78-1N914 | .03 |

| Inductor* | 680uH | 1 (or 2*) | 580-22R684 | .58 |

| Transistor | PN2222A | 1 (or 2*) | 512-PN2222ABU | .11 |

* FSK mode requires two PN2222A transistors and two 1K resistors.

The Radio Shack audio transformers shown in the K7SZL circuit should not be used. The quality of these transformers varies and you can no longer expect to be installing a .6H inductor. If you build the Audio filter order two of the 680uH inductors to replace the Radio Shack transformers.

511-TL071CN Data sheet link http://www.st.com/stonline/books/pdf/docs/2296.pdf 512-PN2222ABU Data sheet link http://www.fairchildsemi.com/ds/PN/PN2222A.pdf

Heil Headset Reviews

Bob Heil – CEO and Founder of Heil Sound

Bob’s life mission is to have fun and bring LOTS of people along for the trip. Bob barely got through grade school and then started making more money than his teachers by playing the (Hammond) organ. Then Bob became a pimp for his high school gym teacher (Sarah can fill you in on the details). Bob had 50+ years of “just OK” life until God sent him a red headed bundle of joy along with her bundle of joy and together they have more fun than a couple of squirrels in a nut forest.

Heil Sound, Ltd. was founded by Bob Heil in 1966. Bob pioneered the live sound industry with clients such as the Grateful Dead, the Who, Joe Walsh, Peter Frampton, Jeff Beck and scores of major touring acts of the 60’s and 70’s. Bob and Heil Sound have won numerous awards over the years, including the first ever “Pioneer Award” from the Audio Engineering Society, and the Parnelli Award.

In 2007, Bob was invited into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame to put up a display of his historically important gear, including the first modular console (the Mavis) his custom quadraphonic mixer (for the Quadraphenia tour) and the very first Heil Talk Box. No manufacturer has ever been invited into the Rock Hall before.

The Night That Modern Live Sound Was Born: Bob Heil & The Grateful Dead (From Performing Musician)

I have used Heil Headsets for years and consider them excellent value for money. The HC-5 cartridge suits my voice perfectly and works for me looking for rare DX. I would highly recommend Heil products. Three more reviews are below.

Heil Headset Review – Three reviews

I’ve used many headsets and microphones over the years. This combination is near perfection. They are comfortable and the HC-5 dynamic element sounds great. The Heil is an excellent headset & very comfortable. When I first opened the box and held the headset in my hands the size of the headset, microphone boom and element enclosure caused a bit of concern. The sturdy (and substantial) mic boom is mounted on one of the two full-sized, closed cup, circum-aural headphones. Was all this plastic, vinyl and steel a bit too much to wear?

The headband suspension self-adjusts and no knobs or click stops are provided. As if made for my head, the headband fell right into place with just the right amount of tension. The headbands fit me perfectly with no bending or adjustment. Once positioned the whole thing stays in place comfortably. Very nice! A set of cloth earpiece covers are provided if that is your preference.

The ear cups attenuate a substantial amount of room noise and allow total focus on the incoming audio. Despite its robust size the Pro Set Plus is not heavy. After hours of wearing them they are still comfortable. The microphone boom requires a bit of persuasive force to bend and rotate it into position. This is a one-time affair, and it hasn’t budged a millimetre since. A small foam windscreen slides over the element housing and adds to the girth of the mic. For those who like a small, discrete-looking microphone this is not for you.

Compared to other studio-quality headphones, the audio is quite good. This is a nice sounding communications headset. Received audio is crisp and clear with ample low, mid and high frequency response. However headphone volume is a bit less than my other phones at the same receiver setting. This is not a big issue since simply increasing the volume level is the solution. The closed ear cups effectively reduce feedback when monitoring your transmitted audio or making EQ adjustments. The phase reversal switch added something to tinker and experiment with.

The HC-5 microphone element has a pleasing frequency response and has a somewhat full sound with a moderate amount of low end. It is not quite as robust sounding as the Heil Goldline full-range element, but gets good audio reports for it’s smooth and clear audio quality. The HC-4 element is also built-in and a small slide switch changes the active element. This element is harsh sounding and favours the mid and higher frequencies – as intended. I’ll save this one for DX work.

Interfacing with my Kenwood TS-940S was easy using the optional adapter cable. You’ll also need a PTT switch – an easy project. A ¼” stereo phone jack is standard on the Kenwood, so receiver audio was plug and play. I also had no difficulty feeding microphone audio into a pre-amp and an EQ for audio experimentation. The mic connection is by 1/8” mono plug and a suitable adapter was easily found in my parts box. An ample length of wire is provided so you can move around your operating position. I like the Heil Pro Set Plus and this is a fine addition to my shack. The construction and audio quality are excellent and should provide years of use.

73, N2KEN.

The Pro Set Plus very nicely compliments my Kenwood TS-2000. The feel and fit is very comfortable. I am wearing them as I write this, and they have been on my head now for about 3 hours. If not for the microphone being in view when I glance down, I’d forget they were on my head.

Sound quality. I have used many headphones over the years for various applications. The sound quality in the Heil P-S-P is among the best I have ever listened to. The Phase reverse is quite effective. I prefer the “B” setting.

Microphone: Without being redundant with the specs and functions that others mentioned already, the elements in the boom mike on this headset are downright fabulous. The DX /FullRangetoggle is a nice touch and as well effective.

Quality: This Headset is attractively made and I find the design configuration to be perfect (for my Melon at least). It’s very apparent that there was no corner cutting done here. The headset also comes with ear covers [put them on the headset, not your own ears :-)) ] and a Mic “poppy” cover. I employ both. If you want a top notch headset/mic combo, I believe you need not look further than the Heil Pro Set Plus. Money well spent.

73, Dennis NC2F

This is it–the ideal context/DX headset. This is a fabulous headset. If you’re a serious DXer or Contester, buy a set. I’ve been a long-time, not-always-happy Heil customer. I’ve owned three of their headsets prior to this one: One of the open-air sets and two of the Pros. I didn’t care for the feel of the open air set (personal preference) and had a problem with the wiring being flaky in one ear. Both the Pros failed mechanically (ear piece fell off) within a few months. One failed within 30 days.

Honestly, I thought that I was done with Heil products. That thought was a very disappointing for me because I loved the HC-4 audio. Figured it was back to a desk mike for me.

Since then, Bob Heil convinced me to try his new Pro-Set Plus. I’ve now made a bunch of QSOs and run half a dozen contests with this set. I started out REALLY sceptical and worried that I was going to break off yet another earpiece. As time went by, I worried less. By the end of a contest when my eyes are pretty bleary, I’m not thinking about being careful with the headset when I put it on or take it off, so I’ve got some really “honest” hours on this set. I love ’em. Plain and simple.

This set is comfortable to wear for hours at a stretch. They lay well on your ears and the band is comfy for many hours at a stretch on the top of your head. The physical adjustability of the mike is perfect. The weight of the set is a great balance of feeling substantial and “worth” the money with airy comfort.

The ear pieces, though. That’s what I was worried about. I already knew the other stuff was good. Bob’s redesign of the connecting mechanism seems to have yielded exactly the results he (and his customers) desired. When I’m thoughtful, I use both hands to take the set off. When I’ve been trying to break the TN pileup with no success and I strip the phones off my head one-handed, well, I’ve put the set to test and it’s stood up beautifully.

There’s nothing I can add about the microphone’s performance that you haven’t read in a dozen other places. It’s premiere. The speakers are further improved from the Pro-Set. I really, really, REALLY like the speakers in these headphones. I think that you will, too. Another minor, positive note: The cord from the phones to the rig is of ample length.(about 8 feet) so that I can roll around the shack without worry of jerking the phones off my head (ever had that one happen to you?!?). I love the quick connect to the mike input on the rig. When the cord gets tangled it takes 5 seconds to disconnect, untangle and reconnect. Very nice.

So, I’m a fan of this product. Bob Heil has won me as a fan with his personal service, superb product performance, and successful redesign. The mechanical aspects of this set now match the near-legendary talk/listen audio performance.

73 de K7VI

Amateur Radio Websites

Amateur Radio Websites

Some great websites for Ham radio information and Logging Programs

AC6V – The reference site for ham radio, 700 Topics, 6000 Links and 132 pages

DX4Win – The most popular general purpose Logging program

N1MM – The best Contest Logging program

Logger 32 – Excellent Free Logging Program

Ham Radio Deluxe – Excellent Logging program

W6EL – Propagation prediction program (and it’s free!)

VE7CC – Packet Cluster program (and it’s free!)

CQ Magazine – The CQ Magazine awards and contest website

ARRL DXCC Awards – The ARRL DXCC awards and contest website

eHam – Great website for general Information

DX Summit – Live DX Cluster spots from around the world

73, Lee ZL2AL

All About Amateur Radio

Amateur radio

Amateur radio, often called ham radio, is a hobby enjoyed by many people throughout the world. An amateur radio operator, ham, or radio amateur uses two-way radio to communicate with other radio amateurs, for recreation or self-edification. The origin of the word “ham” is unknown.

As of 2004 there were about 3 million hams worldwide with about 700,000 in the USA, 600,000 in Japan, 140,000 each in South Korea and Thailand, 57,000 in Canada, 70,000 in Germany, 60,000 in UK, 11,000 in Sweden, and 5,000 in Norway.

Mrs. Bharathi Prasad using her call sign VU4RBI demonstrates Amateur Radio to local students in Port Blair, Andaman Islands, a few days before the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake

Governance and amateur radio societies

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) governs the allocation of communications frequencies world-wide, with participation by each nation by representation from their communications regulation authority. National communications regulators have some liberty to restrict access to these frequencies, or to award additional allocations as long as radio services in other countries do not suffer interference.

In some countries, specific emission types are restricted to certain parts of the radio spectrum, and in most other countries, International Amateur Radio Union (IARU) member societies adopt voluntary plans to concentrate modes of transmission in specific frequency allocations within IARU guidelines, to ensure most effective use of available spectrum.

Many countries have their own national (non-government) amateur radio society that coordinates with the communications regulation authority for the benefit of all Amateurs. The oldest of these societies is the Wireless Institute of Australia, formed in 1910; other notable societies are the Radio Society of Great Britain, the American Radio Relay League, and Radio Amateurs of Canada.

How to become a Ham

In most countries, amateur radio operators are required to pass a test in order to be licensed, unlike other personal radio services such as CB radio, General Mobile Radio Service, or Family Radio Service / PMR446. In return, hams are granted operating privileges in allocated segments of the entire radio frequency spectrum using a wide variety of communication techniques.

Once licensed, the radio amateur is issued a callsign by its government. This callsign is unique to the operator and is often a source of pride. The holder of a callsign uses it on the air to legally identify the operator or station during any and all radio communications.

In many countries, amateurs are required to pass an examination to demonstrate technical knowledge, operating competence and awareness of legal and regulatory requirements, in order to avoid interference with other amateurs and other radio services. In the majority of countries, there are a series of exams available, progressively more challenging and granting progressively more privileges in terms of frequency availability, power output, and permitted experimentation.

In many countries, amateur licensing is a routine civil administrative matter, with considerable worldwide improvement in the past 15 years. In some countries, however, amateur licensing is either inordinately bureaucratic (e.g. India), or amateurs must undergo difficult security approval (e.g. Iran). A handful of countries, currently only Yemen and North Korea, simply do not permit their citizens to operate amateur radio stations, although in both cases a handful of foreign visitors have been permitted to obtain amateur licenses in the past decade.

A further difficulty occurs in developing countries, where licensing structures are often copied from European countries and annual license fees can be prohibitive in terms of local incomes. This is a particular problem in Africa and to a lesser extent in poorer parts of Asia and Latin America. Small countries or those with weak administrative structures may not have a national licensing scheme and may require amateurs to take the licensing exams of a foreign country in lieu.

US Licensing

Amateur licensing in theUnited Statesserves as an example of the way some countries award different levels of amateur radio licenses based on knowledge and telegraphy skill. TheUnited Statessystem has evolved into three-levels of license. The entry-level license, known as Technician, is awarded after an applicant successfully completes a 35-question multiple choice written examination. The license grants operating privileges on all bands above 50 MHz. A Technician who passes a 5 word-per-minute Morse code test is further granted privileges in portions of the 10-, 15-, 40-, and 80-meter amateur bands. The next grade, known as General, requires passage of the Technician test, the 5 word-per-minute telegraphy test, as well as a 35-question multiple-choice General exam. General-class licensees are granted privileges on portions of all amateur HF bands, in addition to the Technician privileges. The topUSlicense class is Amateur Extra. The Extra class license requires the same tests as General plus a third multiple-choice exam. This exam has 50 questions. Those with Amateur Extra licenses are granted privileges on allUSamateur bands.

Morse Code requirement

Commercial and military use of Morse Code radiotelegraphy has almost completely disappeared. As a result, there is a growing demand for Morse testing to be dropped from amateur radio licensing requirements. Until recently, amateurs operating in the short-, medium-, or longwave bands were required by international regulation to pass a Morse code telegraphy exam.

At the 2003 World Radio communication Conference (WRC-03)[1][2] this requirement was made optional leaving it up to individual nations to decide whether or not Morse testing should be required. As a result, many nations, e.g. Canada, Japan, many nations of the European and Oceania, have dropped the requirement while others have yet to make a decision (e.g. USA, India, China, most Arab and Caribbean countries). Presently countries dropping the requirement represent 12% of world Amateurs. While some countries are dropping the requirement for an entry level license, countries like Japan chose to maintain the telegraphy test requirement for it’s highest class license. U.S. Amateurs recently commented in favour of keeping the telegraphy test for at least the highest class license by a 55% to 45% margin [3] when answering a request by the FCC to respond to a Notice of Proposed Rule making (RM 05-235). The FCC proposal seeks to remove the telegraphy test requirement for Amateur Radio altogether.

Morse code is normally sent on the ham bands by keying an unmodulated single-frequency transmission on and off. This communication mode is referred to as CW (Continuous Wave). Statistics show Morse Code use (CW) continues to be the second most popular mode on Amateur Radio with use by Amateurs averaging about 30-35%.

Privileges of the Amateur

In contrast to most commercial and personal radio services, most radio amateurs are not restricted to using type-approved equipment, allowing them to home-construct or modify equipment in any way so long as they meet national and international standards on spurious emissions.

As noted, radio amateurs have access to frequency allocations throughout the RF spectrum, enabling choice of frequency to enable effective communication whether across a city, a region, a country, a continent or the whole world regardless of season or time day or night. The short wave bands, or HF, can facilitate worldwide communication, the VHF and UHF bands offer excellent regional communication, and the broad microwave bands have enough space, or bandwidth, for television transmissions and high-speed data networks.

Although permitted power levels are moderate by commercial standards, they are sufficient to enable cross-continental communication even with the least effective antenna systems, and world-wide communications at least occasionally even with moderate antennas. Power limits vary from country to country, for the highest license classes for example, 2 kilowatts in most countries of the former Yugoslavia, 1.5 kilowatts in the United States, 1 kilowatt in Belgium, 750 watts in Germany, 400 watts in the United Kingdom and 150 watts in Oman. Lower license classes are usually restricted to lower power limits; for example the lowest license class in the UK has a limit of just 10 watts.

Some suggest that the amateur portion of the radio spectrum is like a national park: something like the Yosemite of natural phenomenon. Through the licensing requirement, radio amateurs become like trained national park guides and backpackers. Where the backpackers and guides know about the beauty of the parks as well as the rules of engagement with wildlife in the park system, radio amateurs learn to appreciate and respect the beauty of the very limited electromagnetic space and the rules of engagement of human interaction within that space. In contrast, all of humanity benefits from the radio spectrum’s existence, although it can not actually be seen.

What does one do with amateur radio?

An amateur radio operator engaging in two-way communications.

Amateur radio operators enjoy personal two-way communications with friends, family members, and complete strangers, all of whom must also be licensed. They support the larger public community with emergency and disaster communications. Increasing a person’s knowledge of electronics and radio theory as well as radio contesting are also popular aspects of amateur radio.

A good way to get started in amateur radio is to find a club in your area to answer your questions and provide information on getting licensed and then getting on the air. If you are in the U.S., you can find a club near you by going to the American Radio Relay League‘s Affiliated Club Search page.

Radio amateurs use a variety of modes of transmission to communicate with one another. Voice transmissions are the most common way hams communicate with one another, with some types of emission such as frequency modulation (FM) offering high quality audio for local operation where signals are strong, and others such as single side band (SSB) offering more reliable communications when signals are marginal and using smaller amounts of bandwidth.

Radiotelegraphy using Morse code remains surprisingly popular, particularly on the shortwave bands and for experimental work on the microwave bands, with its inherent signal-to-noise ratio advantages. Morse, using internationally agreed code groups, can also facilitate communications between amateurs who do not share a common language. Radiotelegraphy is also popular with home constructors as CW-only transmitters are simple to construct when compared to voice transmitters.

The explosion in personal computing power has led to a boom in digital modes such as radio teletype, which a generation ago required cumbersome and expensive specialist equipment. Hams led in the development of packet radio, which has since been augmented by more specialized modes such as PSK31 which is designed to facilitate real-time, low-power communications on the shortwave bands. Other modes, such as the WSJT suite, are aimed at extremely marginal propagation modes including meteor scatter and moonbounce or Earth-Moon-Earth (EME).

Similarly, fast scan amateur television, once considered rather esoteric, has exploded in popularity thanks to cheap camcorders and good quality video cards in home computers. Because of the wide bandwidth and stable signals required, it is limited in range to at most 100 km (about 62 miles) in normal conditions.

Most of the modes noted above rely on the simplex communication mode, that is direct, radio-to-radio communication. On VHF and higher frequencies, automated relay stations, or repeaters, are used to increase range. Repeaters are usually located on the top of a mountain or tall building. A repeater allows the radio amateur to communicate over hundreds of square miles using only a relatively low power hand-held transceiver. Repeaters can also be linked together, either by use of other amateur radio bands, by wireline, or, increasingly via the Internet.

While many hams just enjoy talking to friends, others pursue interests such as providing communications for a community emergency response team; antenna theory; communication via amateur satellites ; disaster response; severe weather spotting; DX communication over thousands of miles using the ionosphere to refract radio waves; the Internet Radio Linking Project (IRLP) which is a composite network of radio and the Internet; Automatic Position Reporting System (APRS), which is a system of remote positioning that uses GPS; Contesting; the sport of Amateur Radio Direction Finding; High Speed Telegraphy; or low-power operation.

Most hams have a room or area in their home which is dedicated to their radio and ancillary test equipment, known as the “shack” in ham slang.

Emergency and public service communications

In times of crisis and natural disasters, ham radio is often used as a means of emergency communication when wire line and other conventional means of communications fail. Recent examples include the 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center in Manhattan, the 2003 North America blackout and Hurricane Katrina in September, 2005, where amateur radio was used to coordinate disaster relief activities when other systems failed.

On September 2, 2004, ham radio was used to inform weather forecasters with information on Hurricane Frances live from the Bahamas. On December 26, 2004, an earthquake and resulting tsunami across the Indian Ocean wiped out all communications with the Andaman Islands, except for a DX-pedition that provided as a means to coordinate relief efforts.

The largest disaster response by U.S. amateur radio operators was during Hurricane Katrina which first made landfall as a Category 1 hurricane just north of Miami,Florida on August 25, 2005. More than a thousand ham operators from all over the U.S.converged on the Gulf Coast in an effort to provide emergency communications assistance.

In the United States, there are two methods of organizing amateur radio emergency communications. The Amateur Radio Emergency Service (ARES), sponsored by the ARRL, and the Radio Amateur Civil Emergency Service (RACES), usually organized by municipal or county governments. RACES authorization comes from Part 97.407 of the FCC regulations.

In the United Kingdom, RAYNET, the Radio Amateur Emergency Network, and the RSGB, provide the organisational backbone of their amateur radio emergency communications groups.

In New Zealand the New Zealand Association of Radio Transmitters (NZART) provides the AREC – Amateur Radio Emergency Communications (formerly Amateur Radio Emergency Corps) in the role. They won the New Zealand National Search and Rescue award in 2001 for their long commitment to Search and Rescue in NZ.

Amateurs are often professionally involved in areas which complement their hobby, such as electronics, emergency services, or aviation. This often sees hams as being at the forefront of the development of ‘STSP’ (Short Term Special Purpose) repeater systems and other complex radio linking systems able to easily be inserted by trampers or aircraft into a search area. Being able to provide VHF or UHF radio into an emergency or disaster area means that teams on the ground can use relatively common and portable handheld radios to liaise with base, or with other agencies. VHF-based communications supported by cross banding or STSP repeaters are gradually replacing portable HF systems because of their flexibility, and the relative portability of their antenna and power systems.

DXing, QSL cards and awards

Many amateurs enjoy trying to contact stations in as many different parts of the world as they can on shortwave bands, or over as great a range as possible on the higher bands, a pursuit which is generally known as DXing.

Traditionally radio amateurs exchange QSL cards with other stations, to provide written confirmation of a conversation (QSO). These are required for many amateur operating awards, and many amateurs also enjoy collecting them simply for the pleasure of doing so.

The number of operating awards available is literally in the thousands. The most popular awards are the Worked All States award, usually the first award amateurs in the United States aim for, the Worked All Continents award, also an entry level award on the shortwave bands, and the more challenging Worked All Zones and DX Century Club (DXCC) awards. DXCC is the most popular awards programme, with the entry level requiring amateurs to contact 100 of the (as of 2005) 335 recognized countries and territories in the world, which leads on to a series of operating challenges of increasing difficulty. Many awards are available for contacting amateurs in a particular country, region or city.

Certain parts of the world have very few radio amateurs. As a result, when a station with a rare ID comes on the air, radio amateurs flock to communicate with it. Often amateurs will travel specifically to a country or island, in what is known as a DX-pedition, to activate it. Big DX-peditions can make as many as 100,000 individual contacts in a few weeks.

A group of amateur radio operators during DXpedition to The Gambia in October 2003.

A group of amateur radio operators during DXpedition to The Gambia in October 2003.

Many amateurs also enjoy contacting the many special event stations on the air. Set up to commemorate special occurrences, they often issue distinctive QSLs or certificates. Some use unusual prefixes, such as the call signs with “96” that amateurs in the US State of Georgia could use during the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, or the OO prefix used by Belgian amateurs in 2005 to commemorate their nation’s 175th anniversary. Many amateurs decorate their radio “shacks” with these certificates.

Some hams enjoy attempting to communicate distances with very low power. Signals on the order of 5 watts or less are heard all over the world by these QRP (low power) operators. Some amateurs never use more than a few watts of transmit power. By setting up efficient antennas and using expert operating techniques, they can make regular international contacts and get immense satisfaction from their achievements.

Contesting

A compact ham shack in Central London, England

Contesting is another activity that has garnered interest in the ham community. During a period of time (normally 24 to 48 hours) a ham tries to successfully communicate with as many other amateur radio stations as possible. Different contests have different emphases, with some aimed at chasing DX stations, or stations in a particular country or continent. In some the focus is on operating a station running on emergency power (i.e. portable generators or batteries) to contact other such stations (Field Day), to simulate hurricane or other emergency disaster conditions.

In some contests all operating modes are permitted, while others may be limited to single mode such as voice or CW (Continuous Wave, more commonly called Morse Code). Often, hams join together to form contest teams.

Many hams enjoy casually gaining a few points in a contest, other chasing rare stations who are more likely to make an appearance in these events, others try to set the best possible score using a very limited home station. The serious competitors spend a lot of time in training, spend a lot of money in building up a world class station, and will often travel to a rare country or prime geographical location in order to win.

Vintage Radio

Amplitude Modulation is a mode and an activity that enjoys status as a nostalgic specialty on the shortwave ham bands (1.8 – 29 mHz, or just above AM broadcast band to just beyond the CB band), and draws a wide range of enthusiasts from rock star Joe Walsh, WB6ACU, to the Federal Communications Commission’s Riley Hollingsworth, K4ZDH.

Participating Station, “Heavy Metal Rally”

Conversations are often configured as “round tables” where several participants spend time developing and presenting their thoughts in a storytelling fashion. Listeners reflect on each transmission much as families did when they listened to the old wooden floor console in the early days of radio. Many find this style of communicating more satisfying than the rapid-fire style of operating that can seem rushed and shallow by comparison.

Much of the conversation revolves around do-it-yourself experimentation, repairs, and restoration of popular, vintage vacuum-tube equipment, which has been rising in value because of nostalgic demand. But contemporary transceivers also include AM among modes, and can sound quite good on transmit and receive as a way to encourage a newcomer to check in and introduce themselves.

Frequencies to look for AM activity include 1885, 1930, 3885, 7285, 14286 and 21425, and often include “special event” stations using unique call signs, such as W3F, [4] K3L [5] and W3R [6], The Radio History Society’s station pictured at right. The sound and visual impact of vintage radio are powerful lures.

VHF, UHF and microwave weak-signal operation

While many radio amateurs use use VHF or UHF frequencies primarily for local communications, other amateurs build up more sophisticated systems to communicate over as wide a range as possible.

Despite the common misconception of ‘line of sight’ a VHF signal transmitted from a walkie-talkie (or as hams call it a Handi-talkie or HT for short) will typically travel about 5-10 km depending on terrain, and with a low power home station and a simple antenna to around 50 km. With a large antenna system like a long yagi, and higher power (typically 100 or more watts) contacts of around 1000 km are common. Such operators seek to exploit the limits of the frequencies’ usual characteristics looking to learn and experiment with radio technology. They also seek to take advantage of “band openings” where due to various natural occurrences, radio emissions can travel well over their normal characteristics. There are numerous causes for these band openings and many hams listen for hours to take advantage of their rare manifestations, which may be of fleeting duration.

Some openings are caused by intense excitement of the upper atmosphere, known as the ionosphere. Other band openings are caused by a weather phenomenon known as an inversion layer, where cold air traps hot air beneath it, which forces the radio emission to travel over long weather layers. Radio signals can travel hundreds or even thousands of kilometres due to these weather layers.

Others bounce their signals off the moon (see moonbounce). The return signal is heard by other hams who have equipment suitable for EME (earth-moon-earth) operation, as it is known. The antennas normally required can range from parabolic dishes of up to 10 metres in diameter to an array of directional (usually of the yagi type) antennas.

Digital signal processing has revolutionised weak signal communications by radio amateurs. Using freely available software tools and modern computers, radio amateurs can achieve results they would only have dreamed of only 10 years earlier. For example, reflecting signals off the moon, once the realm of only the very best equipped amateur stations, has become feasible for much more modest stations. Instead of a large dish or an array of 8 antennas, it has become possible for stations with 400 to 1000 watts transmit power and a single well designed antenna to make contacts using moonbounce.

Portable operations

Licensed amateurs often take portable equipment with them when travelling, whether in their luggage or fitted into their cruising yachts, caravans or other vehicles. On long-distance expeditions and adventures such equipment allows them to stay in touch with other amateurs, reporting progress, arrival and sometimes exchanging safety messages along the way.

Many hams at fixed locations are pleased to hear directly from such travellers. From in a yacht in mid-ocean or a 4×4 inside the Arctic Circle, a friendly voice and the chance of a kind fellow-enthusiast sending an e-mail home is very well received.

See maritime mobile amateur radio for further details about operation in this way at sea.

Some countries’ amateur radio licences allow for phone patching, or the direct connection of amateur transceivers to telephone lines. Thus a traveller may be able to call another amateur station and, via a phone patch, speak directly with someone else by telephone. [7]

Mr Kamal Edirisinghe from Sri Lanka operating portable Amateur Radio station south of Stockholm,Sweden

Low power operations

There is a sub-culture of amateur radio operators who concentrate on building and operating radios that operate at low power. This activity goes by the name QRP which is an international Q code for “reduce power”. QRP operators use less than 5 watts output on Morse Code and 10 watts on voice.

Operators can carry small portable QRP tranceivers on their person.

An international organization that promotes this activity is called the QRP Amateur Radio Club International [8] (QRPARCI).

Many records for low power communications over great distances have been set using slow speed telegraphy sent and received by computer [9].

Past, present, and future

Despite all these exciting specialities many hams enjoy the informal contacts, long discussions or “Rag Chewing”, or round table “nets”, whether by voice, Morse code, or computer keyboard.

Even with the advent of the Internet, interest in amateur radio has not diminished in countries with an advanced communications infrastructure. This may be because hams enjoy communicating using the simplest hardware possible, as well as finding the most technically advanced way, advancing the art of radio communication at both ends, frequently beyond what professionals are willing to try to risk.

Nonetheless, Voice over IP (VoIP) is also finding its way into amateur radio. Programs like Echolink, the Internet Radio Linking Project and app rpt/Asterisk use VoIP to tie hams with computers into radio repeaters across the globe. This nascent use is finding applications in emergency services as well, as an alternative to expensive (and sometime fallible) public safety trunking systems.

Some critics point out that in traditional strongholds such as Japan, the United States and Western Europe, amateur populations are ageing Supporters counter that this merely reflects demographic reality in these ageing countries, and in any case is an ethnocentric position. In China and Eastern Europe, young amateur populations are growing rapidly despite equally unfavourable demographics, and young people are also flocking to the hobby in rapidly developing regions such as India, Thailand, Malaysia and the Arabian Peninsula.

Amateur radio innovations and technology