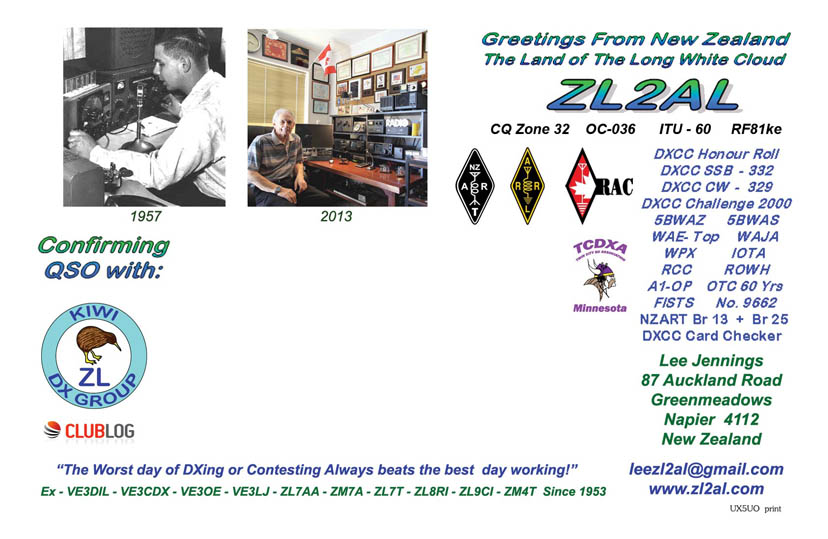

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE WORLD OF DX by Lee Jennings ZL2AL

DXing is addictive

The greatest lure in amateur radio is to contact someone else in another country. When you first start out into the world of DXing, DX may be 100km but later you will work into every corner of the planet. With some hams, it becomes an absolute obsession and they will go to any length to contact that country they haven‘t worked yet. For others, it is a pleasure to rag chew with an amateur in a foreign country and to learn more about that country and its culture. DXers often end up meeting other DXers when they travel and many lifelong friendships are made this way. DXing is a competitive sport. You will find out the moment that you hear some rare DX that a thousand other hams heard that same station and are also calling at the same instant. The problem is that many of your competitors are outstanding operators with high power, excellent antenna systems and vast experience. Most of your competitors are average operators with average stations and antennas and they are easy to compete with. You just have to be a bit more cunning with your skills but eventually you can work up to competing with the top group. That rare DXpedition will usually work the big guns first and then you can easily make the contact at the end of their stay at the rare location.

Currently there are 340 DXCC “Entities “eligible for the ARRL DXCC award program. DXCC is the premier award in ham radio and entry to the “Club” may be gained by working and confirming 100 entities. An Entity can be as large as Australia or as small as St Peter and Paul Rocks out in the South Atlantic Ocean. There are rules that govern what constitutes an “Entity“ and they may be found on the ARRL Website where you can find the rules for the various awards and download the application forms. CQ Magazine in the USA that runs the Worked All Zones awards program and sponsors major contests throughout the year has the rules on their web- site also. Usually you start off with trying to work the first one hundred countries or entities and that will be a milestone for you. It will teach you how to get involved with a pileup and how to be a bit cunning when you do. It will teach you that other DXers in other countries may not have the same sense of fair play as you do. The second 100 countries are a little more difficult to work. Achieving 300 countries is very difficult and will usually take many years for a variety of reasons including sunspot cycles, the rarity of the country and how often its government will allow amateurs to operate there. Currently (2013) there are 340 DXCC Entities and the last 40 entities are extremely difficult to work. Very few ZL amateurs have managed to do lt. But the challenge is always there and it becomes a passion to achieve lt.

Strategies for successful DXing

There are some proven strategies that work. Listen to the operator and find out where he is listening and if he is working split frequencies. Working “split is not difficult, just different. lt‘s a new skill for you to learn. Find out where the thousands of other operators are transmitting and avoid the pack. Position yourself just off the edge of the pack. Refine your timing so that you will be heard in a “gap” rather than in with the pack. Placement and timing is everything. Your signal should be slightly out of the pack so you will be noticed and your call should be slightly out of sync with the pack and just delayed a bit so that he will hear you start your call but not delayed long enough that you are calling on top of the guy the DX station has already decided to work and is answering. Successful experienced DXers are extremely skilful with their timing and consequently work the DX. You may not be heard on your first or second call or even after a few hours of calling. Be patient! Sometimes it‘s an exercise in pure frustration but persistence usually wins and it‘s an absolute joy when you snag that new country. Top level DXing is not easy but you will learn that amateur radio is more than inhabiting your local 2 metre repeater. You will also be rewarded with friendships around the world and an understanding of other cultures.

Is CW worth the effort?

lt really is true that it‘s easier to work DX on CW than on Phone because there are fewer stations clamouring for the attention of a DX station on CW. CW will still be around for the foreseeable future in spite of recent changes in amateur licence regulations around the world. Weak CW signals are more readable than weak Phone signals. Hone your CW skills. DX stations often run 20 wpm or more and while most of them are courteous and will come back to a station calling at 12 or l5wpm, it‘s very satisfying to be able to work them at the speed they‘re calling CQ. Life is much easier with an electronic keyer as it takes the work out of sending your call over and over. There is nothing worse than operating with a pair of uncomfortable, ill fitting, harsh sounding headphones. Invest in a good set of headphones to help you dig out the weak ones and avoid fatigue, A better idea is to buy a quality boom microphone headset with a good sounding microphone cartridge.

Work the contests

Contests can be intimidating, but your best chance for working new countries is often during the DX contests. Contest groups often will activate multi-multi stations in rare countries and they are easy to work. I recall working CN2R in Morocco on 80m a few years ago. Re was S9+ and begging for 80 m contacts and very easy to work. You don‘t do not have to work the entire contest, nor do you have to send in the logs for scoring. Figure out what information they‘re expecting you to exchange with them, either by listening to several contest QSOs or by reading the contest rules on www.contesting.com then just jump in and start working stations.

What bands to operate

The seven popular amateur radio bands offer the DXer propagation to most parts of the world most of the time. When the sunspot count is between the eleven year peaks, the higher bands like 10, 12, 15, 20 M are poor and opportunities are limited. 40M and 80M come into their own and some excellent DXing abounds providing you have good antennas. DXing is more difficult on 80 and 160m because the ambient noise levels are often intolerable in urban areas. When the propagation is right and the bands are open at sunrise and sunset, 80 and 160m can be extremely rewarding with worldwide contacts. We are fortunate here in the Asia Pacific region as many rare DXpeditions take place and are easy to work on the lower bands. When the sunspots reach maximum every eleven years the higher bands are magic. The next peak will be in 2012. 10, 12 and 15m will often be open 24 hours a day and lt is relatively easy to work 100 countries during a weekend contest. Having a ZL call is a wonderful asset. ZLs are reasonably rare in other parts of the world and there are not that many ZL DXers to compete with. ZLs are often the first “real“ DX station that Europeans work. ZL DXers are respected around the world and we have some world class Kiwi DXers amongst us. It is not uncommon to call a CQ on 15 or 20M and generate a pileup of Europeans or North Americans that may go on for hours.

Operating aids

The DXer has far more tools at his disposal than he had 30 or 40 years ago. Then, you heard a rumour, read monthly DX magazines or received a phone call from a trusted friend. You listened daily, you waited and finally you would hear that weak rare station and attempt to work him with primitive valve equipment. Today‘s modern DXers have computers with the Internet based newsgroups, real time packet clusters, propagation prediction programs and information not dreamt of by old timers in the game. Today one knows where and when the rare DX will operate. With a few mouse clicks the modern well equipped station will change the radio to that frequency and mode, track the amplifier to the right band, select the correct antenna system, turn the beam to the heading and set his call up in the logging program in a few seconds. Sounds easy! The reality is that you still have to use your skills to get your call in his electronic logbook. And it doesn‘t get any easier as thousands of other hams have the same technology. Below are some web links to programs and services that will help you work DX.

www.ac6v.com/ -The definitive reference site for ham radio— Over 6000 links.

www.dxatlas.com/ – DX Atlas—A great program for DXCC, WAZ, IOTA info plus brilliant Grayline and path headings.

www.qrz.com – The online address and QSLing data base for most hams around the world.

www.eham.com – A great source of info on general ham radio

www.contesting.com – Keep up to date with international contests

www.dx4win.com/ – Excellent logging program.

www.writelog.com/ – Excellent contest logging program.

www.kc4elo.com/index.htmI – Free but very good logging program.

www.eqf-software.com/ – Some great logging programs.

www.qsl.net/w6elprop/ – Propagation prediction (and it‘s free!).

www.rchalmas.users.ch – DX Cluster program (and it‘s free!).

www.arrlorg/awards/dxcc/ The ARRL DXCC awards and contest website.

www.dxawards.com/book.html – The K1BV Awards directory listing for 3227 awards.

www.oh2aq.kolumbus.com/ dxs/ – The DX Summit – Live DX cluster spots 24 hours a day.

www.ac6v.com/morseaids.htm – The definitive web page on Morse code—worth going to even if you don‘t understand it or use it!

Packet cluster networks

Packet clusters have been a phenomenon of the DXing world over the past 10 or 15 years. Basically lt works like this. There may be a local Internet based Cluster or VHF packet channel Cluster in a city in Europe somewhere and a group or cluster of hams are connected to it. When someone in the group works a rare station he types into his cluster software the details in the following format: DX 14015 ZD9BV Calling CQ. The last comment is optional. The message or “spot“ immediately appears on the screens of all connected to that cluster. Most clusters are now linked to the internet and there are more than 1000 of them around the world in every populated area. As soon as that spot hits the internet it spreads to all the cluster nodes and you will see it on your screen in your shack. In fact you will see a continuous stream of DX stations, Announcements and WWV information on your screen 24 hours a ay. There are many free programs available. DX packet clusters are a wonderful tool for chasing DX

Minimum-maximum Station gear

There are some facts to consider when you are thinking about investing in equipment for your station.

(1) The Operator on the other end can‘t tell whether you have the latest all singing, all dancing multi featured transceiver costing in excess of $8K or a 30 year old valve radio you picked up at a junk sale for $300. 100W is 100W. Both are equal. The only difference is that the older radio may not have all the latest modern features.

(2) The stations with the 30m towers and stacked 5-el monobanders driven by very large amplifiers will often beat you in a pileup. These are the guys that work the rare DX first and they love doing it. After they have done lt … they go away and let the rest of us work the station. As long as you are aware of the big guns, it‘s not a problem because time will be kind to you.

(3) The stations that have the “best“ sounding audio will always win in a pileup. It is human nature that the DX station will always take the path of least resistance and work the station he can understand and clearly hear the easiest. Best means clean, punchy and standing out from the rest. Commercial broadcast announcers are picked because of their mellow authoritative voices. Be aware of your own limitations and strive for the best audio you can generate. An authoritative voice helps!

(4) With CW – You will need an electronic keyer and clean keying set a bit below the pack‘s general speed. This is better than trying to impress the DX station that your electronic keyer can do 45 wpm with ease. He can‘t! – Well, actually some DX ops can but they are rare.

(5) At the end of the day everything helps, but don‘t get hung up on particular antennas or brands of radio equipment. They are only part of the picture. A good antenna is the second best investment you will ever make. The first is taking the time to learn the techniques and skills of how a rare DX station thinks and operates. A cunning operator will outwit a big antenna every time!

Computer logging

Computer logging programs are almost essential for those who have a large number of QSOs. Over time they become one of the best tools around for keeping things in order. Don‘t start out with a cheap shareware logging program. A key factor in a logging program is to be able to display various award details in DXCC entity order as one has them worked or confirmed. The main prestige awards are DXCC, WAZ, DXCC Challenge, WAS, WAC, IOTA There are thousands of others. When you want to see how your goals are being met, you can look at your statistics right on the computer screen. Computer logging programs are a great time saver because most of them generate data and address labels that will save hours and hours of handwriting. Computer logging can keep track of QSLs sent and received with just a click of the mouse. A really good computer logging program will do all of the above and control your radio, send CW, display your local packet cluster DX spots and print the QSO information directly onto your QSL cards with no labels involved.

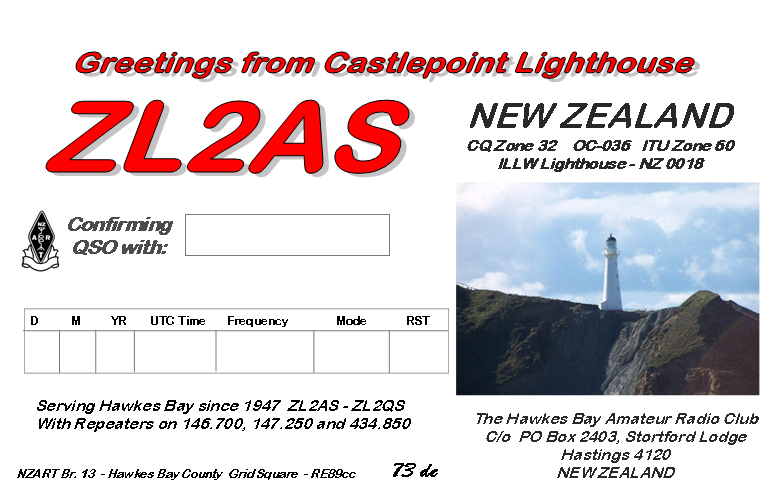

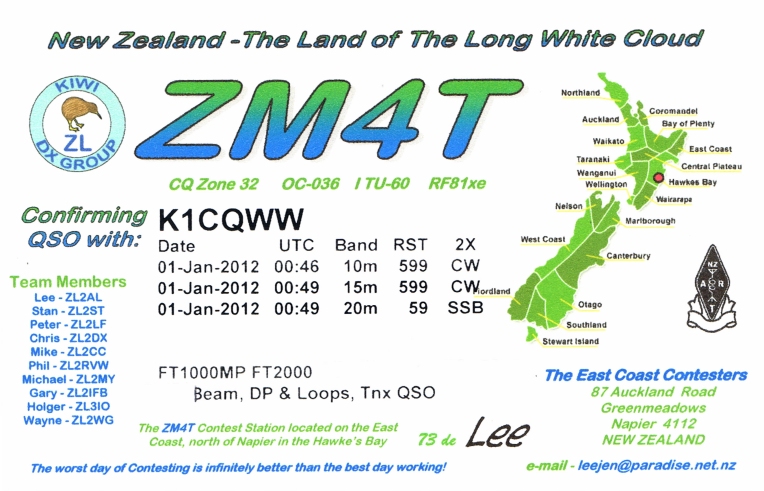

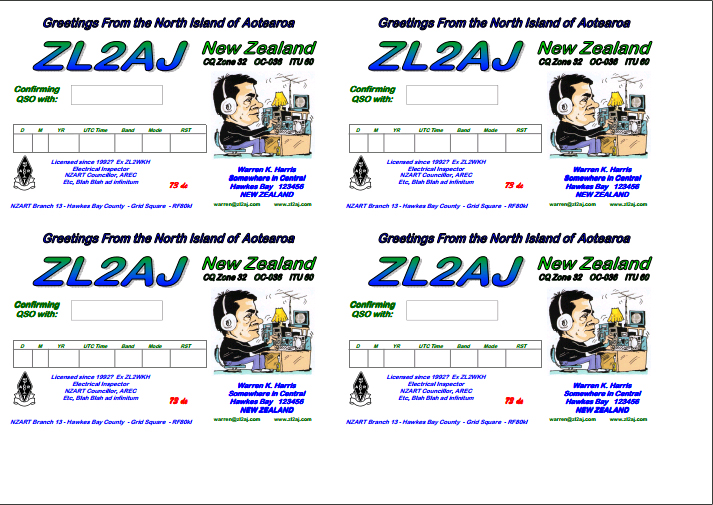

The process of QSLing

If a newcomer to DXing starts out by working DX stations during contests he will quickly learn that he will work key countries multiple times. I would make the bureau one of my first choices The QSL Buro Service here in New Zealand is excellent and lt will save you postage costs. If you use the NZ Buro a lot make a donation every now and then! My best advice is to save your postage dollars and greenstamps (One US Dollar) for your rare station direct QSL requests. Confirming DXCC takes time and by the time one gets close to 100 different confirmed countries, several months or years will pass. There are several systems of filing, and the one that is probably the most common is to keep QSLs in order by DXCC entity. Shoeboxes help and they are inexpensive. There are some neat boxes sold buy the big chain stores here in New Zealand to file photographs in and they are excellent for QSLs. Keeping QSLs in DXCC entity order is the first step in being able to find and sort cards for awards later down the line. Believe me, it is not an easy task to sort a couple of thousand QSLs from scratch. Be smart and start sorting at the very beginning.

Awards and rewards

The ARRL DXCC Program

ARRL DXCC Honour Roll, 5 Band DXCC, WAS, 5BWAS, the DXCC Challenge Award and the CQ WAZ awards are the most prestigious awards in ham radio. Actually, there are over 3200 awards available to wallpaper your shack. Only the above few really measure how well you compete with other DXers around the rest of the world. In fact the list of awards that can be earned for working certain collections of DX stations is almost endless. www.ac6v.com/ will give you a link to the universal awards page. We have some world class DXers in New Zealand but only a few ZLs have managed to achieve the ARRL DXCC Honour Roll award. We now have a authrized ARRL DXCC Card checker in New Zealand which means you do not have to send your precious cards to the USA for verification. Contact Lee ZL2AL [email protected] for further information. Your DXCC QSOs may also be verified online on the ARRLs website LoTW (Logbook of the World)

DXpeditions

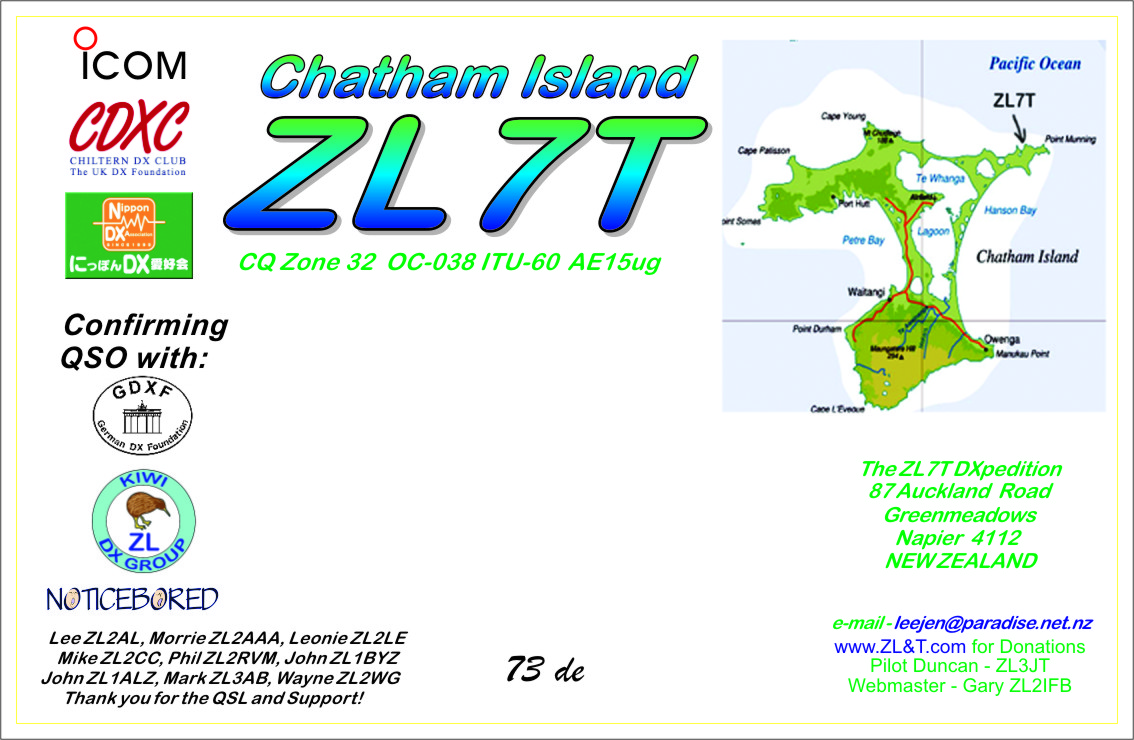

If DXing is an obsession, then DXpeditioners are the lunatic fringe of the DX world. At any given time these are hundreds of amateurs operating from rare locations around the world. You can be assured that there are thousands of others actively planning a DXpedition somewhere and hundreds of thousands of “armchair DXpeditioners“ who would love to go. Planning a major Dxpedition is almost as com- plicated as a NASA mission. Large scale modern DXpeditions can chew through $400,000 or more in no time so it isn‘t a project that can be taken on lightly. New Zealand just happens to have ten or more of some the rarest DXCC entities islands within its territory. ZL7 – Chatham Island, ZL8 – Raoul Island

and ZL9 – Campbell and Auckland Islands are usually in the top 25 most wanted entities. The demand continues unabated and opportunity abounds for ZLs to organize more trips to these desired locations.

It is the experience of a lifetime to participate as an operator on a DXpedition. The camaraderie und experience gained is incomparable. DXpeditions to ZL7 are easily organized, tremendous fun and are to be recommended for gaining experience. When you consider all these factors, it is no wonder that DXing is so popular even though we are at the bottom of the eleven year solar cycle in 2009 there are always rare DX stations around to be worked. As the propagation becomes better over the next few years HF DX will improve. When sunspot cycle number 24 peaks in a few years from now you will experience fabulous world-wide propagation. I am trying to provide tips and information in this section to help you succeed in DXing, whether you are a newcomer 10 DX or a DXing veteran. If you would like to find out more about DXing, contact me at [email protected] and I will be happy to put you in touch with DXers in your area. You should also subscribe to the Google Kiwi DX List reflector for up to the minute information.

The worst day DXing sure beats the best day working!

73, Lee Jennings ZL2AL